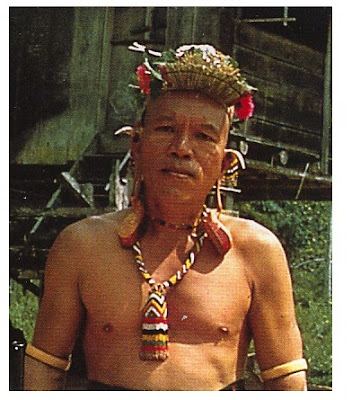

The hornbill is among the most sacred birds to many of the peoples of Sarawak and Kalimantan. The Orang Ulu used to carve hornbill ivory for personal adornment as earrings, worn by men. Hornbill ivory is a delicate material and only a few people are able to carve the fine designs.

Hornbill "ivory" comes from the casque or epithema of the helmeted or "great helmeted" hornbill. Traditionally, this material is designated hornbill ivory with no quotation marks enclosing the word ivory. This is misleading because hornbill "ivory" is keratin whereas ivory that from elephant tusks is chiefly apatite.

The casque is chiefly yellowish white to golden or light brownish yellow, with its top and sides relatively thinly coated by diverse hues of red, which have been described as carmine red, Chinese red, scarlet, orange red or brownish red. The light-colored portion typically has a "blotchy" appearance.

Calao, another name given to hornbills, is used as a modifier for the "ivory" in some literature.

Relatively old carvings, many of which are exquisite, were made for use near the source areas and in China. Belt buckles, bracelets, brooches, combs, ear ornaments, incense burners, pendants, plume holders for hats, rings (especially archers' thumb rings), spoons, snuff bottles, temple vases, and even whole casques were included. In addition, the Japanese carved netsuke from the casques and used thin slivers of the red sheaths for inlay, usually along with other materials such as mother-of-pearl, tortoise shell and some metal. After the middle of the 19th century, hornbill "ivory" was incorporated into such "modern jewelry" as brooches, cuff links, earrings and studs, much of which was fashioned in Canton, chiefly for sale in the Western world.

Helmeted hornbills are native to the rain forest jungles of Southeastern Asia such as Southern Myanmar (formerly Burma), Southern Thailand (formerly Siam) and other parts of the Malay Peninsula, and of Borneo and Sumatra of the East Indies. Casques of the male are used to fashion the pieces treated herein.

The word casque means head-piece or helmet. Birds of the family Bucerotidae, formerly called horned crow or horned pie, were given the name hornbill because they have a horn-like excrescence on their upper mandible that resembles certain helmets. In Malaya, this hornbill is often called the 'Kill your mother-in-law bird" (tebang mertua). This name arose because of its strange call, consisting of a loud toks repeated increasingly faster and ending in wild laughter, which gave rise to an old legend. They say that the helmeted hornbill was once a Malayan who cordially disliked his mother-in-law and finally chopped down the stilts that supported her hut when she was inside it, in order to get rid of her. As punishment for this misdeed, the Gods then changed him into this bird, and condemned him forever to re-live his crime by making the sound of the axe striking the foundation posts, followed by his outburst of unholy glee when the house came crashing down.

The helmeted hornbill is the only hornbill with a solid casque. The casques of other hornbills have spongy interiors. The casque of the adult male helmeted hornbill typically makes up more than 10 per cent of the bird's total weight and is about 10cm high and 5cm wide, a volume large enough for fashioning three snuff bottles. It is dense and takes a fine, lustrous polish. The red hues of the casque comprise only a relatively thin coating on the tops and sides of the upper mandible. They are apparently caused by the birds' rubbing their upper mandibles on their preen glands where the red hues represent natural dyeing by oily secretions from the birds' preen glands. The transition between the reddish zones to the natural yellowish main part of the casque is gradual.

The best hornbill "ivory" is from young mature males. It has to be cleaned and cured adequately as soon as possible after the death of the bird in order to preserve the desired colors and other features. If untreated, the red layer often tends to split away from the rest of the casque and especially under conditions of excessive dryness, it gradually loses colour. However, these changes can be avoided or at least minimised by special treatment, as many of the Chinese carvings demonstrate. Most carving involves the same general procedures as those used for true ivory and vegetable ivory. However, an apparently unique and especially interesting type of carving used by the Chinese for some articles like belt buckles is noteworthy. It involved cutting away of parts of the red layer so the underlying yellow layer exhibited the desired design along with undercutting of the red layer except for a few "connecting posts" so the remaining layers would not separate one from the other. As a result, the red layer was given an attractive translucence. In addition, treatments that appear to reflect utilization of the thermoplastic property of this material have been utilized by some craftsmen.

Historically, carvings from hornbill casques have been found in a Neolithic tomb in Borneo. Early trade with China especially during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and first mentioned recorded in 1371 was based on the fact that many Southeastern Asians wanted something made of this material because they considered it to be an aphrodisiac and a detector of poisons. The increase of virility aspect seems likely to relate to the fact that, like the male narwhal's tusk, the male hornbill's casque appears to be a male characteristic with no function other than to exhibit its male sexuality; the poison detection held that anything made from it would undergo a color change whenever it was in the proximity of poisonous materials, especially anything its owner might ingest. It was only more recently, when Chinese traders discovered some of the fine carvings made from these casques, that hornbill "ivory" gained its rightful place among the highly esteemed materials used for fashioning valuable decorative pieces.

The helmeted hornbill is an endangered species. West Kalimantan (sometimes referred to as Kalbar), which is an Indonesian province of the southwestern part of the island of Borneo, has the helmeted hornbill as its official emblem.

Pictures below showing the Dayak carved hornbill earrings from my collection. The top part of the hornbill beaks has been carved with an anthropomorphic figure, while the inner (or the back) part of the beaks has been incised with stylized "aso" or dog motifs. The red sides of the beaks use similar "aso" motifs with openwork designs.

Hornbill "ivory" comes from the casque or epithema of the helmeted or "great helmeted" hornbill. Traditionally, this material is designated hornbill ivory with no quotation marks enclosing the word ivory. This is misleading because hornbill "ivory" is keratin whereas ivory that from elephant tusks is chiefly apatite.

The casque is chiefly yellowish white to golden or light brownish yellow, with its top and sides relatively thinly coated by diverse hues of red, which have been described as carmine red, Chinese red, scarlet, orange red or brownish red. The light-colored portion typically has a "blotchy" appearance.

Calao, another name given to hornbills, is used as a modifier for the "ivory" in some literature.

Relatively old carvings, many of which are exquisite, were made for use near the source areas and in China. Belt buckles, bracelets, brooches, combs, ear ornaments, incense burners, pendants, plume holders for hats, rings (especially archers' thumb rings), spoons, snuff bottles, temple vases, and even whole casques were included. In addition, the Japanese carved netsuke from the casques and used thin slivers of the red sheaths for inlay, usually along with other materials such as mother-of-pearl, tortoise shell and some metal. After the middle of the 19th century, hornbill "ivory" was incorporated into such "modern jewelry" as brooches, cuff links, earrings and studs, much of which was fashioned in Canton, chiefly for sale in the Western world.

Helmeted hornbills are native to the rain forest jungles of Southeastern Asia such as Southern Myanmar (formerly Burma), Southern Thailand (formerly Siam) and other parts of the Malay Peninsula, and of Borneo and Sumatra of the East Indies. Casques of the male are used to fashion the pieces treated herein.

The word casque means head-piece or helmet. Birds of the family Bucerotidae, formerly called horned crow or horned pie, were given the name hornbill because they have a horn-like excrescence on their upper mandible that resembles certain helmets. In Malaya, this hornbill is often called the 'Kill your mother-in-law bird" (tebang mertua). This name arose because of its strange call, consisting of a loud toks repeated increasingly faster and ending in wild laughter, which gave rise to an old legend. They say that the helmeted hornbill was once a Malayan who cordially disliked his mother-in-law and finally chopped down the stilts that supported her hut when she was inside it, in order to get rid of her. As punishment for this misdeed, the Gods then changed him into this bird, and condemned him forever to re-live his crime by making the sound of the axe striking the foundation posts, followed by his outburst of unholy glee when the house came crashing down.

The helmeted hornbill is the only hornbill with a solid casque. The casques of other hornbills have spongy interiors. The casque of the adult male helmeted hornbill typically makes up more than 10 per cent of the bird's total weight and is about 10cm high and 5cm wide, a volume large enough for fashioning three snuff bottles. It is dense and takes a fine, lustrous polish. The red hues of the casque comprise only a relatively thin coating on the tops and sides of the upper mandible. They are apparently caused by the birds' rubbing their upper mandibles on their preen glands where the red hues represent natural dyeing by oily secretions from the birds' preen glands. The transition between the reddish zones to the natural yellowish main part of the casque is gradual.

The best hornbill "ivory" is from young mature males. It has to be cleaned and cured adequately as soon as possible after the death of the bird in order to preserve the desired colors and other features. If untreated, the red layer often tends to split away from the rest of the casque and especially under conditions of excessive dryness, it gradually loses colour. However, these changes can be avoided or at least minimised by special treatment, as many of the Chinese carvings demonstrate. Most carving involves the same general procedures as those used for true ivory and vegetable ivory. However, an apparently unique and especially interesting type of carving used by the Chinese for some articles like belt buckles is noteworthy. It involved cutting away of parts of the red layer so the underlying yellow layer exhibited the desired design along with undercutting of the red layer except for a few "connecting posts" so the remaining layers would not separate one from the other. As a result, the red layer was given an attractive translucence. In addition, treatments that appear to reflect utilization of the thermoplastic property of this material have been utilized by some craftsmen.

Historically, carvings from hornbill casques have been found in a Neolithic tomb in Borneo. Early trade with China especially during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and first mentioned recorded in 1371 was based on the fact that many Southeastern Asians wanted something made of this material because they considered it to be an aphrodisiac and a detector of poisons. The increase of virility aspect seems likely to relate to the fact that, like the male narwhal's tusk, the male hornbill's casque appears to be a male characteristic with no function other than to exhibit its male sexuality; the poison detection held that anything made from it would undergo a color change whenever it was in the proximity of poisonous materials, especially anything its owner might ingest. It was only more recently, when Chinese traders discovered some of the fine carvings made from these casques, that hornbill "ivory" gained its rightful place among the highly esteemed materials used for fashioning valuable decorative pieces.

The helmeted hornbill is an endangered species. West Kalimantan (sometimes referred to as Kalbar), which is an Indonesian province of the southwestern part of the island of Borneo, has the helmeted hornbill as its official emblem.

Pictures below showing the Dayak carved hornbill earrings from my collection. The top part of the hornbill beaks has been carved with an anthropomorphic figure, while the inner (or the back) part of the beaks has been incised with stylized "aso" or dog motifs. The red sides of the beaks use similar "aso" motifs with openwork designs.